Out of all the types of tea that exist out there, pu’erh is generally one that I discuss the least on One More Steep with yellow tea being, by far, the most rarely discussed if only because of the rarity of the tea itself. But pu’erh is also a tea that I grew up drinking a lot. It’s a staple at dimsum restaurants and a fantastic tea for long tea drinking sessions because a good pu’erh typically resteeps incredibly well.

Pu’erh is one of those teas that seems mysterious to a lot of tea drinker that don’t dabble into more Chinese teas. If your tea cabinet consists primarily of Earl Grey, chamomile, and peppermint, pu’erh probably isn’t one of those teas that is lurking in the cabinet if only because it’s not your jam. In Chinese, pu’erh tea is also called hei cha (literal translation: dark or black tea), which is very different from what western culture calls black tea (which, in Chinese, is called hong cha; with the literal translation of “red tea”).

Pu’erh is a fermented tea – either through time or through a sped-up process – that uses micro-organisms to contribute to the process and the flavour. There’s two primary categories that I will discuss: sheng pu’erh and shou pu’erh. Please keep in mind that I am not an expert on pu’erh tea, and nor do I pretend to be one, and I will be discussing the basics of both sheng and shou pu’erh, as well as similarities of both.

You will also find pu’erh being written as pu’er, pu-erh, pu-er, puerh and puer on the internet. Just to add to any confusion you might have had about this category of tea. For consistency’s sake, you will see that I use pu’erh on One More Steep.

Sheng pu’erh has many other names, as does shou pu’erh.

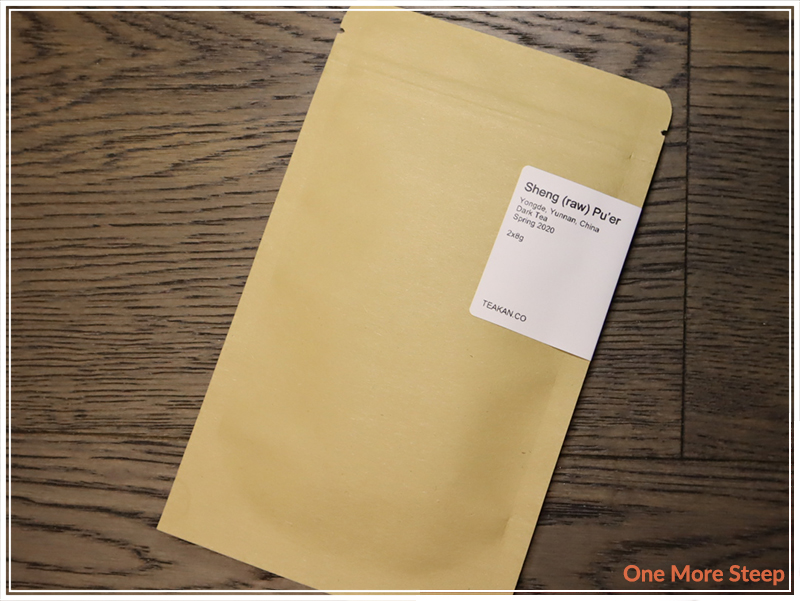

Sheng pu’erh is also referred to as raw or unripe pu’erh/tea, aged or young pu’erh (depending on the age). Sheng pu’erh is allowed to age naturally, and ferment. Sheng pu’erh can be harvested, lightly steamed, pressed into shape (discs, balls, bricks) or left loose – and then left to age intentionally. Typically sheng pu’erh is allowed to age for, at minimum, 10-plus years before they are steeped. The process of producing sheng pu’erh (primarily the time), makes it the more expensive of the two types of pu’erh.

There are a lot of factors that go into producing a good sheng pu’erh and I’m not able to educate you on it (because it’s simply not in my wheelhouse), but intentionally allowing a tea to age also means keeping an eye on things like moisture/humidity that the tea is exposed to – because you want to age the tea… and not grow a pile of mold.

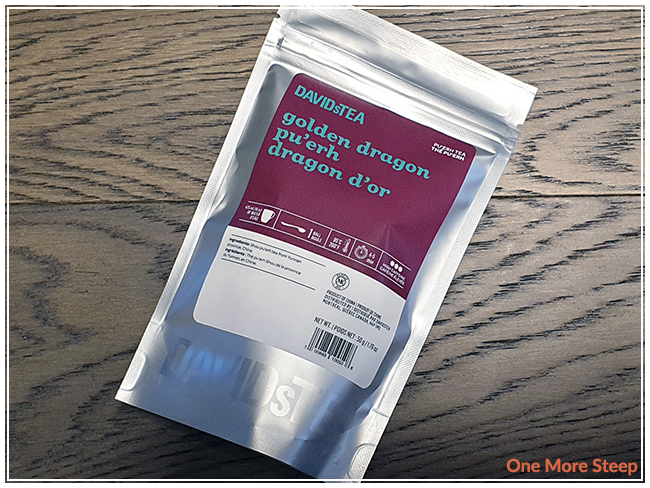

Shou pu’erh on the other hand is a ripe or cooked pu’erh/tea. The production method of shou pu’erh involves creating a large pile of leaves, and intentionally keeping the leaves moist and warm to encourage beneficial bacteria and molds to grow, and then turning the leaves to encourage even fermentation (much like you would turn a compost bin). Once properly ‘cooked’, the leaves can be pressed into shape like sheng pu’erh, but the tea itself is ready-to-drink and no further aging is required.

Shou pu’erh is the “young” version of pu’erh, with the development of the processing method coming into play in the 1970’s with the growing popularity and demand for pu’erh tea. After all, it’s a long time to get a sheng pu’erh to a drinkable state if you’re patiently waiting for the tea to age and ferment. Shou pu’erh fills in that demand by making pu’erh more accessible (less expensive!) in comparison to a slowly aged sheng pu’erh.

As a whole, pu’erh is less accessible in North American markets, but the typical North American tea drinker is also not the primary demographic that consumes pu’erh tea. I find that shopping in person for pu’erh tea is limited to Chinese/Asian grocery stores, and specialty tea shops. If you’re lucky to live in an area with a Chinatown, finding a tea shop that features pu’erh might be within your grasp. If you’re not, then online shopping is always an option! Try to look for online stores that offer samplers or smaller amounts of pu’erh – you don’t want to be venturing into purchasing a whole 500g brick for your first pu’erh adventure.

Pu’erh is fantastic tea to steep – typically a pu’erh is unadulterated, so you don’t have added ingredients or flavourings, making it a great tea to resteep. A pu’erh is a great way to practice gongfu steeping and also grandpa steeping. If you have the option of pu’erh tea at a dimsum restaurant, I’d highly recommend it (that would be usually a grandpa style of steeping tea).

As a whole, pu’erh is often a very rich, dark colour when you steep the leaves. The flavour is honestly very difficult to describe unless you have the tea available to you because there are so many factors that influence the flavour. How long the tea has been aged, how well it was kept (was there too much moisture or humidty, or not enough?). I typically find that pu’erh has a very earthy aroma and flavour to it though, which is likely due to the fermentation process with the microbes.

Two bricks of sheng pu’erh are unlikely to be identical because there’s just so many factors that go into the flavour of the tea during the fermentation process. Shou pu’erh, on the other hand, is more likely to have a consistent flavour because of the process in which it’s made (quicker, not relying on decades of time and changes in conditions). That said, I personally find that sheng pu’erh can be much more complex in flavour because of the time allowance to grow that depth of flavour.

Both sheng and shou pu’erh can be a great tea to enjoy if you’re looking to expand your tea-drinking horizons. Have you tried it before? Do you enjoy pu’erh regularly?